I briefly mentioned in my last missive about my pleasure at having written a booklet essay for the first ever blu-ray release of Chris Thomson's criminally underseen 1985 Australian noir, The Empty Beach. Based on the 1983 novel of the same name by Sydney crime writer Peter Corris, it's not only one of only a handful of Australian crime films centred on a private investigator. It’s arguably also amongst the small pool of noir on the screen Australia has produced.

Since then a few people have reached out to ask me for suggestions of other Australian noir films. There are a few that would be worthy of mentioning - although I would be surprised if anyone can come up with a list longer than you can count off on the fingers of both hands - but there are two that I think are particularly underseen and worthy of mention.

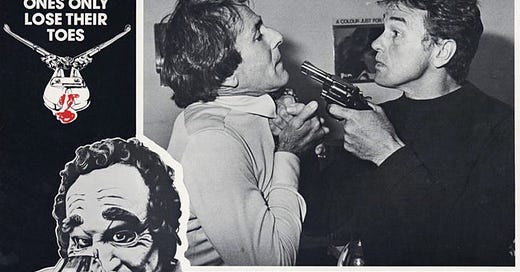

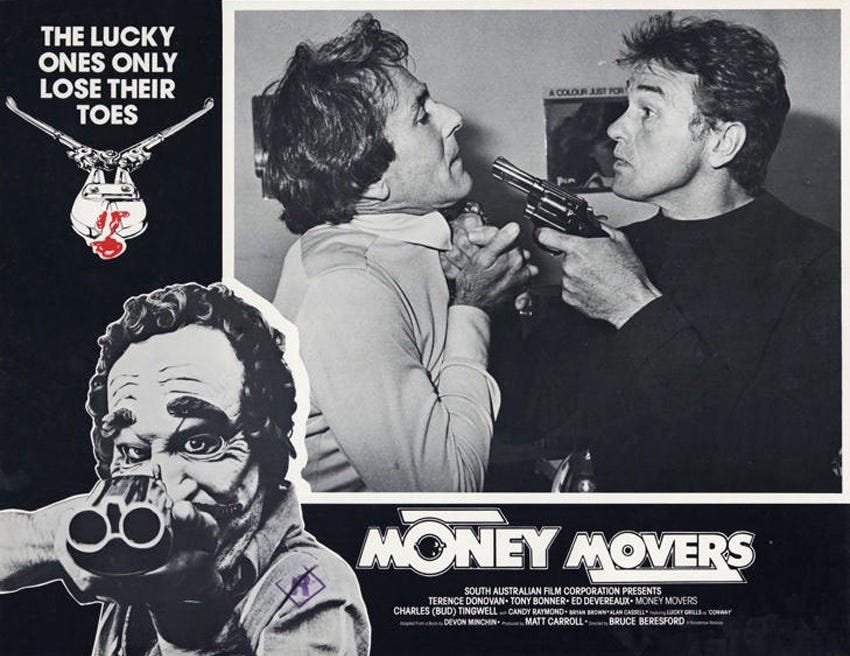

One I’ll save for my next post. For now, I want to talk about Bruce Beresford’s 1978 heist movie, Money Movers.

It was adapted from the 1972 novel, The Money Movers, by Devon Minchin, father of the ferociously right wing Australian Senator, Nick Minchin, and amongst his many commercial exploits, the founder of what was at one time, the country’s largest privately owned security company. Minchin was also something of an novelist with several books to his name, non-fiction as well as fiction, and The Money Movers was apparently loosely based on two armoured car robberies that occurred at Minchin’s company.

The film version completely flopped on release and from what I have read online, Beresford has spent the years since, distancing himself from the work. A pity on both counts as Money Movers was proof Australia could knock out a noir as gritty and multi-layered as the best of them.

The film’s atmosphere is established in the opening scene, muster time in the counting house of Darcy’s Security Services. The armoured car drivers exchange jokes and take a last drag on their cigarettes before going on the weekly bank run. Two of them, Brian Jackson (Bryan Brown) and his brother, Eric (Terence Donovan), head of security at Darcy’s, pause to observe money being unloaded from a truck with particular interest. This is juxtaposed with shots of management, or the “armchair drivers” as those on the shop floor derisively refer to them, and images of the (then) modern paraphernalia of security in operation: mesh grills being electronically lowered, lights flashing, doors being buzzed open.

On the road, one of the trucks parks for the drivers to a take a lunch break. On their return, they are jumped by men wearing clown masks and brandishing sawn off shotguns. One driver is shot. The other, Dick Martin (Ed Devereaux), gives a good account of himself before being clubbed unconscious. His resistance marks him out someone who won’t be intimidated.

The robbers are next seen pulling into an old garage. No sooner have they cracked open their first celebratory beers than they are finished off by a henchman working for the mastermind behind the operation, Henderson (another veteran Australian actor, Charles ‘Bud’ Tingwell), who has no intention of sharing the take.

Meanwhile across town, a secretary hands the CEO of Darcy’s a note (made up of cut and pasted newspaper letters, no less), informing them the counting house will soon be robbed. The note forces management to fast track new security measures - if they can get them past the opposition of the local trade union. They are not the only ones worried. The Jackson brothers along with the emphysemic head of the local union, Gallagher (Ray Marshall), are planning to rob the counting house and are not happy with the prospect of any criminal competition.

Eric has been working on the job for five years, taking his time, making sure everything is right, much to the chagrin of his hot-headed brother. Now their hand has been forced and they have to move quickly. As they talk, the three men leaf through the personnel files of new recruits to the company for some clue about who might be trying to muscle in on their job. Their main suspect is Leo Bassett (Tony Bonnor), a young urbane man patently out of place patrolling industrial back lots in the middle of the night.

To bank roll their plan, Eric knocks over a cosmetics factory patrolled by Darcy’s, in the process killing one of his own security guards. Next he prowls Bassett’s pad for evidence linking him to the note, unaware it is also under surveillance by Henderson’s goons. They capture Jackson, find the replica of the Darcys’ armoured car he and his brother are working on, and realise what they are up to. With the help of some bolt cutters, Henderson persuades the Jackson brothers to cut him in as a partner. Henderson’s terms are simple: he seconds some of his men to help out with the job and takes 60 percent of anything stolen in exchange for helping get the brothers out of the country when it is over.

Using a union meeting as cover, the brothers attempt the robbery. It almost comes off until Dick Martin fresh from the beating he endured during his earlier attempt to protect the company’s money, notices something amiss. Needless to say, like most heist films it all ends very badly.

The feel of the Money Movers is straight down the line noir. While it is filmed in Sydney, there’s not an opera house or expanse of blue water in sight. Instead the action takes place in truck lots, factory floors, container yards and neon lit streets. On the few occasions the movie takes us into larger, more brightly lit locations, the characters seem tense and uneasy.

The most enjoyable aspect of Money Movers is the way Beresford executes the classic noir theme of the paper-thin line between good and bad. Corruption is so pervasive, so matter a fact, it’s hardly commented on. Management complain about the girls in the counting room slipping notes into their underwear. Before he’ll lift a finger, the policeman investigating the note threatening to rob the counting house casually shakes down Darcy’s human relations manager for a bribe. “Might be a bit costly,” he says about chasing down leads. “Not real orthodox stuff.”

The blurring of morality extends to modern business methods. Darcy’s management are more worried about the impact of the latest armoured car robbery on their insurance premiums than the safety of their employees. The CEO ponders aloud whether they should try and get some younger guards, “ex-Vietnam boys”, only to be informed they’re considered too trigger happy. Besides getting a better class of guard would break unofficial company policy only to employ applicants who fail an unofficial test that they won’t get bored with the job.

Flush with money made from selling drugs, liquor and sex to visiting American GIs during the Vietnam War, the seventies were a time of massive corruption across much of Australia. The nexus between criminals, commerce, sections of the labour movement and police was tight. Illegal businesses flourished often under the direct patronage of corrupt police. Against these forces, amateurs like Eric and Brian Jackson don’t stand a chance, no matter how quick on their feet or good with their fists they are.

Beresford doesn’t waste much time explaining why these men want to rob their employer. For the older brother, an ex-racing car driver now trapped in an unhappy marriage, it’s about recapturing some sense of being on the edge. His younger brother just wants the fast track to a good life. All we know about the aging union hack Gallagher is an old black and white photograph of an Asian woman and his promise to come back to her.

The film combines classic elements of noir with some uniquely Australian characteristics. The class divide is starkly drawn, reinforced throughout by images of wealth and money. The Australian economy was on the verge of recession in the late seventies, unions represented over half the working population (now it is just over 13 percent), and the view that management and workers were not on the same side wasn’t nearly as anachronistic as it sounds now. The desire of the Jackson brothers to rip management off, to get what they have, is just a given. Even the crime boss Henderson is a victim of the economic times, masterminding armed robberies for funds to refurbish his textile factory that went belly up when government lifted import restrictions.

Given the milieu it depicts, not surprisingly Money Movers has a male feel and aggression and violence are always close to the surface. Perhaps one of the reasons the film has somewhat languished. The men are unquestionably in charge; the women relegated to harassed secretaries, angry wives, and bits on the side. Leo Bassett, the man the Jackson brothers suspect of being behind the note, is not only an outsider, he’s branded a ‘poofter’ by Brian Jackson because it states in his personnel file that he likes music and poetry – the kiss of death in seventies Australian working class male culture.

Those who do try to do their job and refuse to compromise, like ex-cop Martin, get little in return. At the film’s end, as Martin is being wheeled out of the counting house on an ambulance gurney after nearly being killed foiling the Jackson brother’s robbery, the corrupt cop Ross tells him: “Get over this and they’ll stick a medal on you and put you back on award wages”. A little piece of metal and a minimum wage job – the best deal a hero is likely to get in Money Movers.

Mussolini: Son of the Century

I cannot tell you how much my life has improved since I stopped chasing the dopamine hit of event television. Seriously, if I get around to catching the latest ‘it’ show, all well and good. If I don’t, I largely don’t give it a second thought. I am free to watch what I want and what I am watching at the moment is Mussolini: Son of the Century.

Mussolini: Son of the Century is an Italian/French co-production, directed by an Englishman, Joe Wright, and based on a book by Italian academic, Antonio Scurati. The eight part series, which I am just over half way through, focuses on Mussolini’s early political career, from the founding of his right wing political party, Fasci Italiani, in 1919, up until his seizure of power in 1922 and his early years as Italy’s strongman.

I know it’s hard to move these days without some cultural commentator or historian pointing out the historical parallels between the 1920s and 1930s and the absolute shit show that is the international scene right now. Particularly the rapidly looming spectre of fascism in the United States. And Mussolini: Son of the Century is capital H history screaming at you take to wake the hell up and realise what is going at the moment.

Mussolini, brilliantly portrayed by Luca Marinelli, is a manipulative, scheming, backstabbing, two faced wannabe dictator. But importantly, he has an unerring faith in his own destiny and powers. He and the people around him recognise that the institutions of the old post WWI Italy and weak and sclerotic and that the day will belong to the group that is prepared to take fast, decisive action that combines polemics with ruthless violence. That Mussolini is able to get away with it is because the old ruling class is complacent, underestimate him, and believe they can accommodate his momentum within their crumbling structures.

Amidst all his setbacks and political stumbles, the series shows Mussolini exhibiting an absolutely crystal clear view of what needs to be done, from which he never fundamentally deviates. The established political elite, including the left, on the other hand, are complacent, disunited, and uncertain in their response. Ultimately, they also believe Mussolini and the people around him are too stupid to succeed. In this respect, one of the real take homes from the show for me, is a sense that it is the Italian fascists that Trump’s MAGA enablers are basing themselves on, not the Nazis. I suspect this is part of the reason why the show has been unable to secure any stream rights in the United States. In Australia, it is free to watch on-demand on SBS television.

Yeah, I know all of this is simplifying very complex historical forces. But, seriously, I challenge you to come away from watching this show without wanting to punch the American friend on your social media feed who is still posting ‘I’m with her’ memes, as Trump and Musk systematically dissemble America’s cultural, political and economic institutions.

Apart from its serious political message, Mussolini: Son of the Century is also fast moving and entertaining. I have read that Wright's vision for the series was a fusion of Man with a Movie Camera, an 1929 experimental documentary about a city in the 1920s Soviet Union, from morning until night, Brian De Palma’s 1984 film Scarface, and 1990s rave culture. Each episode veers between the characters engaging in serious political diatribe and, at times, almost slapstick theatrics. The funniest and most perceptive moments come when Mussolini breaks the fourth wall to admit to an insecurity or mistake, to share a joke at the expense of one of the other characters, or or to let the audience in on his real intentions. It took me precisely one episode of Kevin Spacey doing this in House of Cards, to stop watching that show. But in Mussolini: Son of the Century, it works for me, big time. Hopefully, by the time I get to the end of the series, I’ll have figured out why.

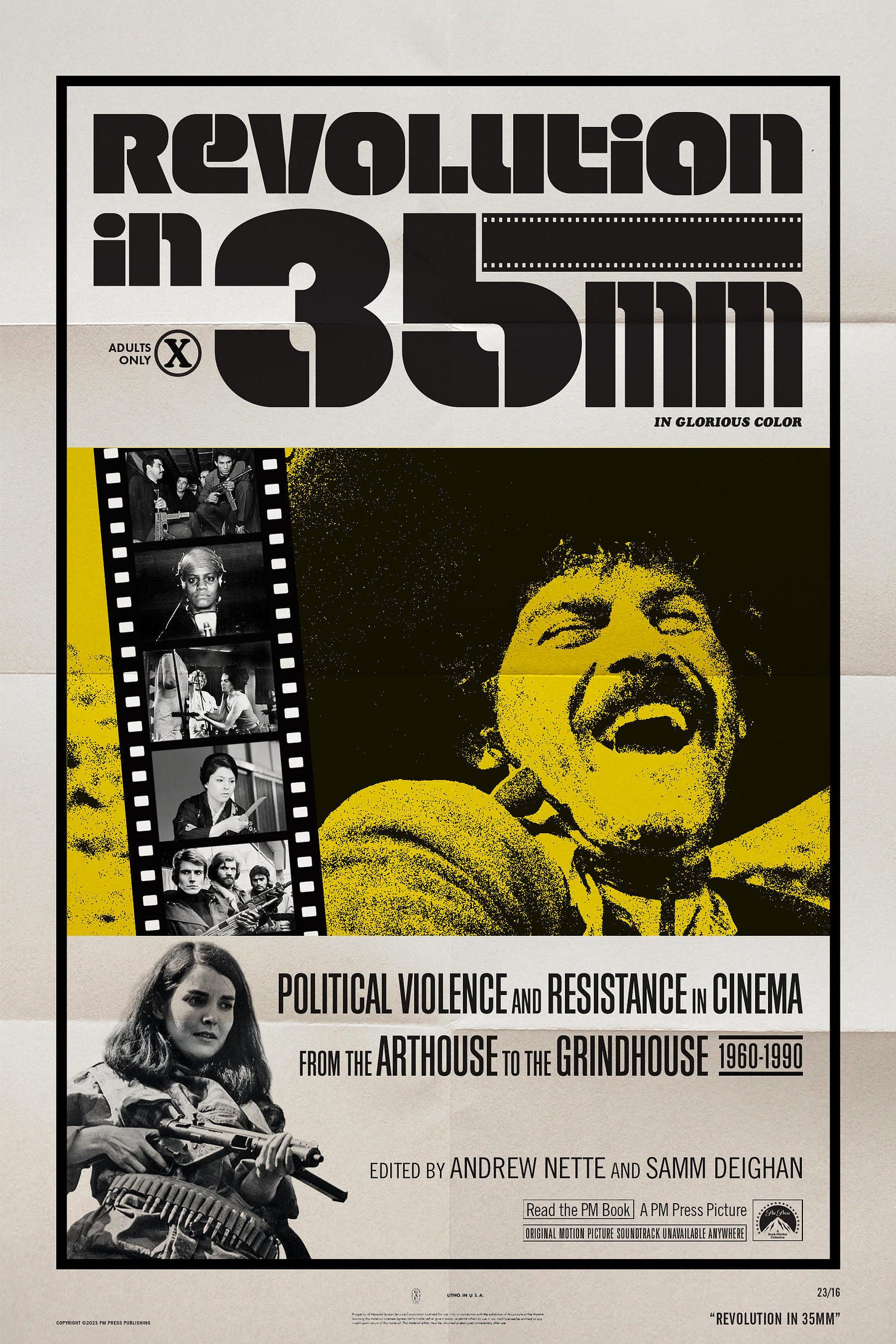

Revolution in 35mm: Political Violence and Resistance in Cinema from the Arthouse to the Grindhouse, 1960-1990

My latest book, co-edited with Samm Deighan, Revolution in 35mm: Political Violence and Resistance in Cinema from the Arthouse to the Grindhouse, 1960-1990, is available from online and physical book shops. You can also pick it up as a physical and ebook from the publisher, PM Press, at this link here.

Watched Money Movers a few months back, cracking little film. Definitely benefits from most of the characters being sweaty, desperate, and not as young as they used to be — a more slickly produced film with 'cooler', more competent people wouldn't be nearly as effective.

Two more excellent Reviews

Have bookmarked Mussolini SOTC to watch next followingthis Review.Hope to be able to track down the Film Money Matters in UK streaming sites or DVD