I don’t know whether Jack Gold’s 1970 film The Reckoning can be labelled noir or neo-noir. I rewatched it with the intention of counting it as part of my Noirvember viewing. I included it in the end but, yes, maybe debatable whether it belows there. It doesn’t really matter, because it’s bloody brilliant either way. A proto Get Carter that appeared a year earlier, like Ted Lewis’s film the narrative spine features a brutal, damaged man who returns to the northern England working class town of his youth on a mission of revenge.

Michael Marler (Nicol Williamson – best known for his role as Merlin in John Boorman’s 1981 film, Excalibur) is a hard living up and coming middle manager in a London firm that sells accounting machinery. He has fancy clothes, a Jaguar sports car, a beautiful home, and a beautiful upper class wife (Ann Bell), with whom he has an intense and deceptively complex relationship. He is a flagrant womaniser, with no loyalty, who despises his managers at the company at the same time sucking up to them. He is also working class Irish, a past he has worked hard to tear himself away from. In the process of doing so he has had to shed so much of what he is, and this has made him lost, angry and bitter.

As the film opens, Marler’s firm is facing a steep decline in sales due to the advent of computers. As he is fitting up another middle manager to take the fall for the problem, Marler gets a phone call that his elderly father has had a heart attack and is near death. He reluctantly jumps into his Jaguar and at terrifying speed returns to the grim, working class northern English city of Liverpool, the place he fled from when he was 17, first into the army and then into business, and has seldom returned since.

Marler’s father dies just before he arrives. Paying his last respects to the corpse, however, Marler finds heavy bruising on the body. He does a bit of investigating and discovers the heart attack that killed his father was preceded by a vicious beating from a Teddy Boy in a Liverpool bar. It was not reported by the elderly men who were with his father, who witnessed it, because they hate the police. And his late father’s GP (played by Godfrey Quigley, who had a small role in Get Carter) has also hushed it up for a quiet life.

The discovery propels Marler to re-examine his life since leaving Liverpool, his relationship with his left wing Irish nationalist father and his working class roots. Having identified the young thug who beat his father up, Marler also ponders seeking revenge. At first, he shakes off this urge and returns to London. But his hatred for his English managers at the firm he works for and the polite upper class social circle that his wife has gathered around them, quickly comes to the surface. At a party organised by his wife, his speech reverts to its earlier working class Liverpudlian tones, and he punches out a senior business associate. The action threatens his career at the firm and reinforces the fact that his English bosses have no loyalty towards him and keep him around mainly because they find his ruthless business sense useful. This realisation leads Marler to the decision that he has no choice but to return to Liverpool and kill the young man he holds responsible for the death of his father.

For those of you who have not seen it, I won’t discuss the film further, because it’s worth the effort to track it down and watch (on this occasion I viewed the Indicator Films re-release, which is accompanied by some greater bonus features). The Reckoning is based on a book by Patrick Hall and adapted for the screen by John McGrath who had a long career in British television. The only other film I have seen by the Gold, the director, Aces High, a strange, very hardboiled 1976 retelling of R. C. Sherriff’s Journey’s End, but set in a squadron of biplanes in World War I, rather than among the infantry as the play originally was.

It is impossible not to talk about The Reckoning in the same breath as Get Carter. Both films are about men who have left their working class roots to become successful in their various professions in London, and who are then forced to come home due to a family tragedy. Liverpool, like Newcastle in Get Carter, is depicted as a tough, rainswept working class town. And much like Jack Carter, Marler is intensely uncomfortable in its bleak surrounds, the tiny council house that his family still live in, with its wood panelling and flocked wallpaper, the raucous smokey pubs they drink in, with their bad torch singers and cheap bingo games. But gradually, Marler starts to re-acclimatise, a process helped by having a one night stand with a local woman, Joyce (wonderfully portrayed by Rachel Roberts), and who is also intensely discontented with life.

And, of course, the two stories depict changing class relations in English at the end of the 1960s. This includes the gradual emergence of the more internationalist conservative entrepreneurial class that would eventually propel Margaret Thatcher to victory a decade later, as well as the way in which economic change was slowly starting to flow into the regions, bringing with it developments such as new sexual relations and consumerism. The Reckoning is particularly excellent portrayal of this; the way in which the sons of the working class went off the university, graduated, made money, but were left feeling strangely incomplete as they realise how much of themselves that they have had to sacrifice to get where they are. “I feel like I’ve been play acting since the minute I left home,” is how Marler puts it to Joyce.

Lastly, both films are about revenge. In this regard The Reckoning is in many respects more satisfying. Unlike Jack Carter, Marler has made himself into a middle class businessman and has no idea how to go about killing a man. As a professional gangster Carter is adept at dishing out violence. Marler is not and the process of deciding what he will do leads him to examine his masculinity and everything he has believed in up until now, which makes the narrative far more cathartic.

As Marler’s mum says to him when he is about to return to London the second time. “You’re a bad lad, Mick.” He gives her a loving look and replies, “I always was.”

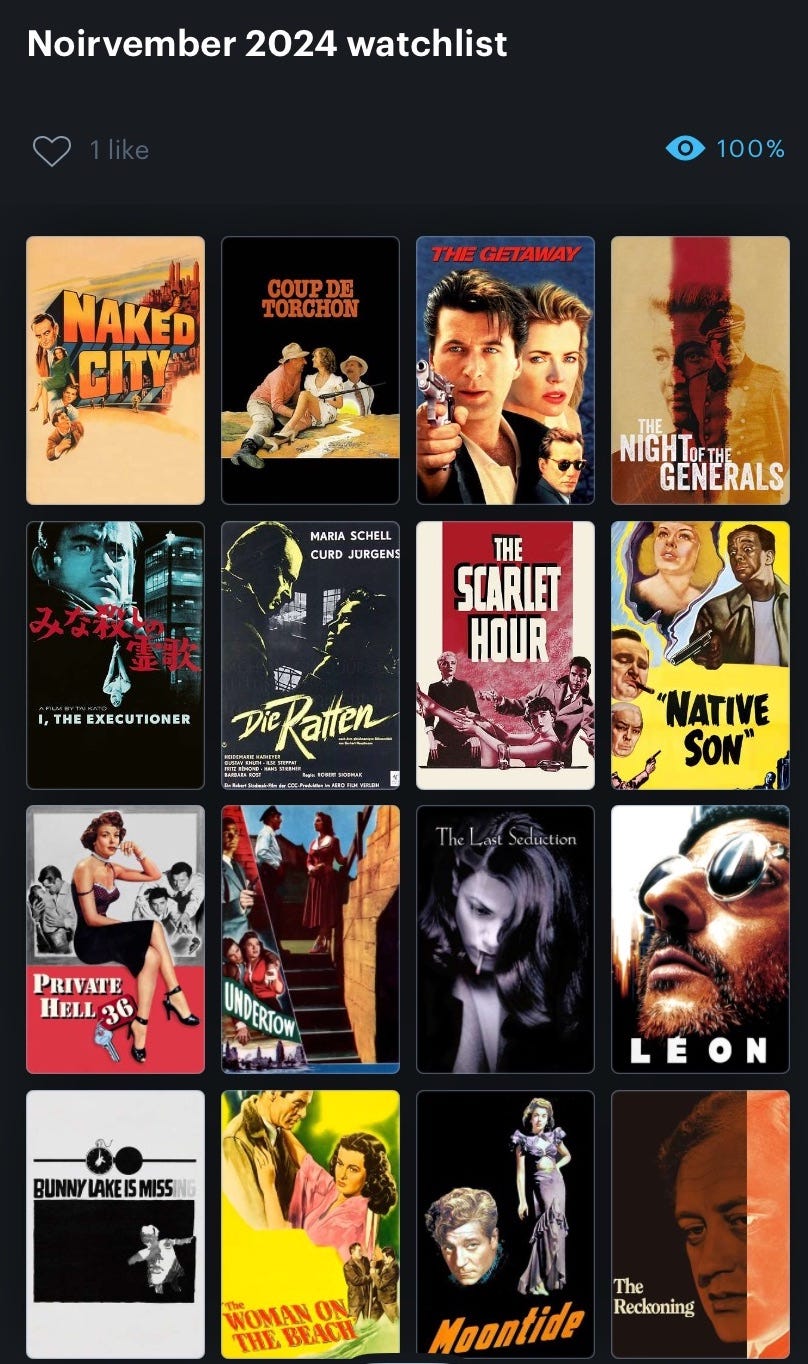

Noirvember watchlist

That’s a wrap for Noirvember 2024. If you are so inclined you can check out my Letterboxd watchlist here.

Revolution in 35mm: Political Violence and Resistance in Cinema from the Arthouse to the Grindhouse, 1960-1990

A reminder that my latest PM Press book, co-edited with Samm Deighan, Revolution in 35mm: Political Violence and Resistance in Cinema from the Arthouse to the Grindhouse, 1960-1990 is available from online and physical book shops. You can also pick it up as a physical and ebook from the publisher at this link here.

PM Press are having a sale for the month of December and you can pick up Revolution in 35mm and all their other books and ebooks at half price with the coupon code GIFT at pmpress.org.

Love Get Carter (& the book/s it’s based on) but never heard of The Reckoning - I’ll search it out

Never heard of this one, will be checking it out this weekend! Thanks 🙏