Violent Road: A Californian Wages of Fear?

The French have remade Henri-Georges Clouzot’s 1953 classic, The Wages of Fear. The film, directed by Julien Leclercq, also called The Wages of Fear, will be available in March on Netflix, and provides a temporary stay of execution in terms of my desire to end our household’s subscription to this otherwise lacklustre streaming service.

I thought this was the third film version of the 1950 novel by Georges Arnaud, along with William Friedkin’s Sorcerer (1977). But there is actually a fourth unofficial film version, a late American film noir, Violent Road, sometimes known as Hell’s Highway, released in 1958.

Violent Road was directed by Howard W. Koch, better known as a producer, and based on a script by Richard Landau, who mainly worked in television, and Don Martin. Martin penned one of my favourite discoveries of Noirvember 2023, Shakedown (1950), a cracking tale involving a corrupt tabloid news photographer who falls foul of the organised crime interests he plays against each other in order to get ahead in the newsroom.

Although there is acknowledgement of such, Landau and Martin unashamedly rip off the Arnaud’s story, placing it somewhere in California. When a test rocket misfires and destroys a nearby school, the powers that be in the town the rocket factory is based in, decree the factory that made it needs to relocate. The factory’s desperate management have three days to move three truckloads of deadly and highly unstable rocket fuel safely to another location across rough desert mountain road.

Who would be desperate enough to undertake the task?

Enter a tough trucker cum drifter, Barton (Brian Keith). Barton assembles a team of five men to do the job for $5000 each: a traumatised WWII veteran; a young hot rod driver; a serial gambler; a man who needs the money to go to college; and the scientist who developed the fuel, and whose wife and two children were killed in the rocket crash that destroyed the school.

While the story does not go anywhere near full Wages of Fear/Sorcerer, I found Violent Road surprisingly good. I won’t go into too much detail about it here, but what I really appreciated was the plot devices the writers came up with, no doubt on a shoestring budget, to obstruct the safe passage of the fuel trucks: everything from mechanical failure and fatigue, to rockslides, an out of control school bus, and local law enforcement who refuse to let the trucks and their drivers stop in their town for the night en route to their destination

The character development is, at best, sketchy. But this doesn’t really matter too much. What the story establishes is the motivation of the men who agree to drive the trucks. All five are pushed by the need for money to achieve the American dream that is otherwise beyond their financial reach. This is a pretty standard film noir trope, but in Violent Road it is elevated by what I consider to be the changes that crept into the genre around 1958, generally seen as the dividing point between classic and late film noir.

Have you ever noticed how film noir from around 1958 onwards looks different. They are less lush, more washed out and garish. The pacing and plot lines feel more somehow more tabloid and sleazier. And while I wouldn’t say that there is necessarily more sex in film noir from 1958 onwards, it does feel closer to the surface. There is also a real sense that the social, economic and political space created in the late 1940s and very early 1950s by the wrecking ball of WWII had constricted. By the mid-fifties the state and its dominant social relations had regrouped and were on the counterattack in the form of the red scare and campaigns to establish moral order. The pressures arising from this shift weigh heavily on the characters in post 1958 film noir. Like Barton and his fellow truckers, these people appear fit to burst from the accumulated pent up sexual and economic anxiety. And they will do anything to get a leg up, like drive a truckload of dangerous chemicals on a suicide mission across the desert.

As of writing this post, there is a decent burn of Violent Road on YouTube here, if you want to check it out.

In the meantime, would some enterprising publisher PLEASE re-release Arnaud’s 1950 in English? It is currently out of print and even the tattiest second hand copies cost a fortune.

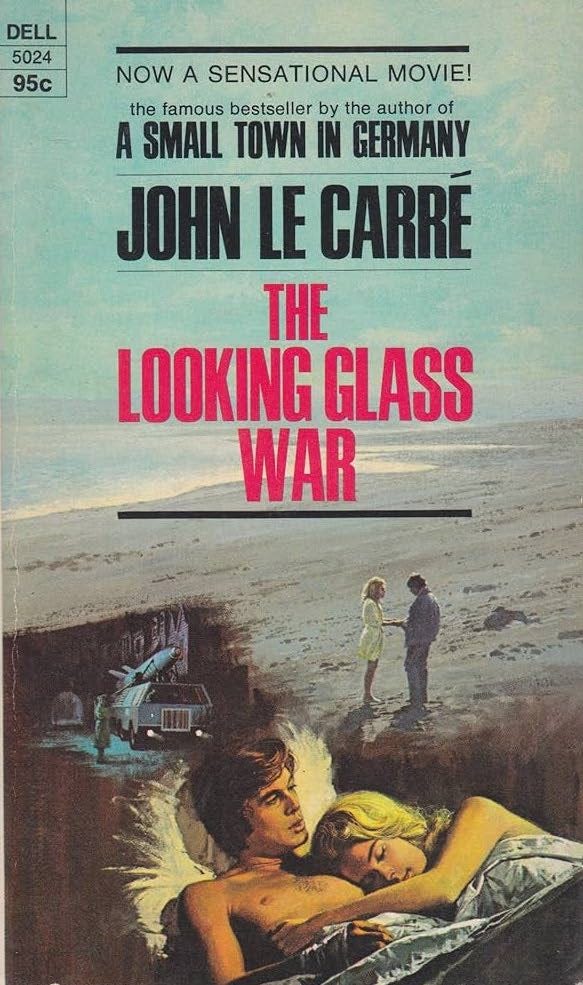

The Looking Glass War

Is The Looking Glass War one of Le Carré best books?

I am on record at my old Pulp Curry site as saying that one of the best screen adaptations of a John le Carré work is Frank R. Pierson’s 1970 adaptation of The Looking Glass War, published in 1965.

A recent very long solo drive from Brisbane to Melbourne provided the occasion to listen to The Looking Glass War on audio book, which gave me a totally new appreciation of just how good the novel is.

George Smiley doesn’t make an appearance in film version, but he does pop up at various points in the book. The story involves an organisation called the Department, a low rent version and fierce rival of Smiley’s Circus, headed up by a pompous old man called Leclerc. Leclerc believes he may have stumbled across a plan by Moscow to base missiles on East German soil, which if true could represent a Cold War escalation of Cuban Missile Crisis proportions. To try and verify the information, Leclerc gets the go ahead from his political masters to send a man over the border, Leiser, a Polish man living in London who worked for British intelligence in WWII.

Like the film version, one of the aspects of the novel that really stands out is its depiction of the WWII generation. Men simultaneously damaged & strangely sustained their war service, an experience that was both horrific and the highlight of their lives. They are emotionally stunted and trapped in their old worldview and way of doing things. And, in the context of their job as spies, this gets in the way of their espionage activities, with lethal consequences.

The novel is also a wonderful exploration of the world of analogue spy craft, including numerous detailed scenes in which Leiser is trained in unarmed combat and the use of radio equipment, etc. It is a must read for all those who, like me, appreciate a good dose of what I termed in a previous Substack post on the 1973 film The Day of the Jackal, as logistics porn.

And, as I noted in my Pulp Curry piece, The Looking Glass War is possibly Carré’s bleakest novel. It almost has a noir sensibility. It is not just that the espionage game involves a series of looking glasses, surfaces that are so reflective that its practitioners merely see themselves and their own biases, what they desperately want to be true, instead of what is. The whole intelligence project is morally bankrupt, and ultimately, futile, more of a danger to world peace than peace than its preserver.

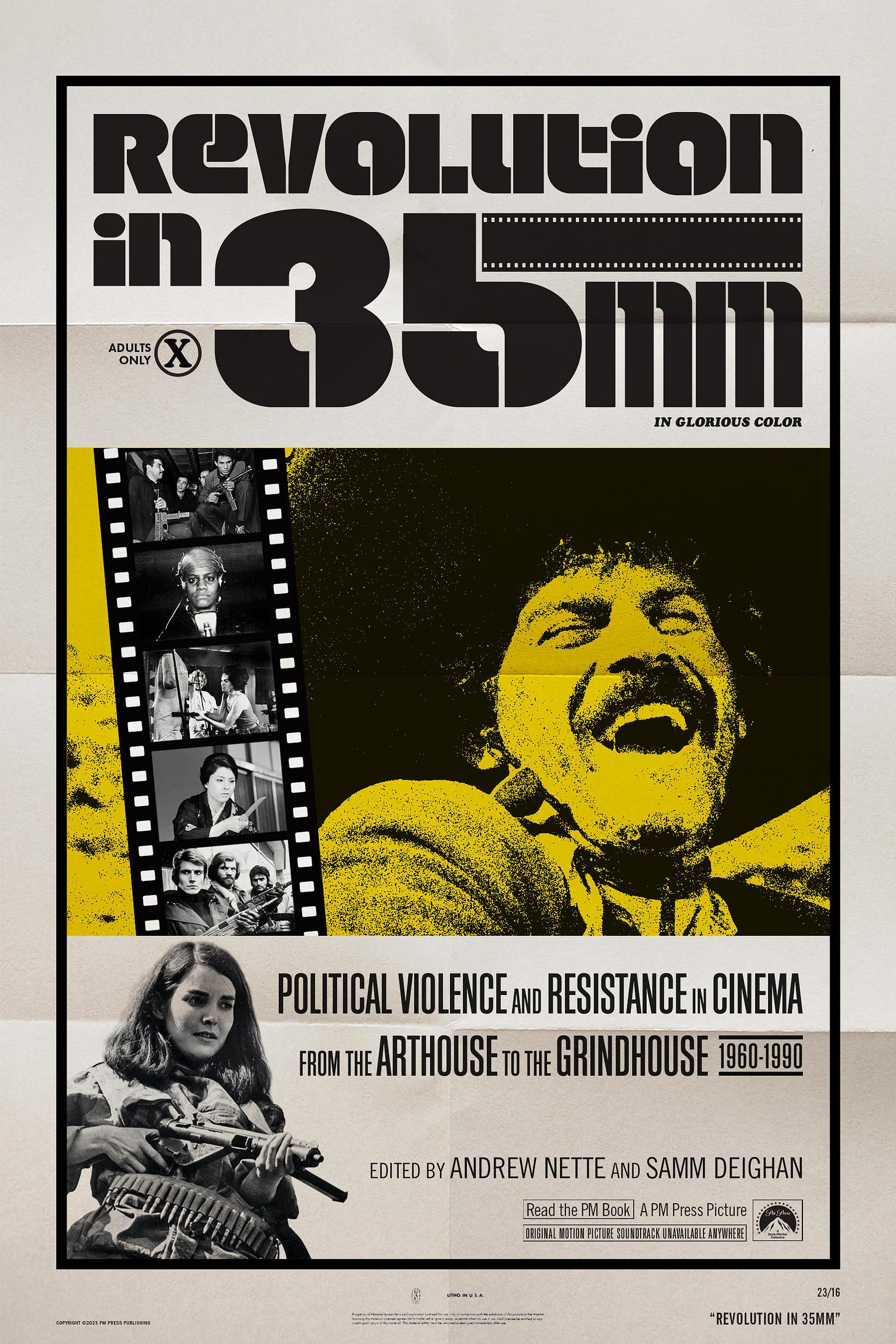

Pre-orders open for Revolution in 35mm Political Violence and Resistance in Cinema from the Arthouse to the Grindhouse, 1960-1990

The new book I have co-edited with the wonderful New York-based film critic, Samm Deighan, is available for pre-order at the website of the publisher, PM Press.

I’m very proud of this book, which is also going to be beautifully illustrated in full colour, and in addition to writing by Samm and myself, includes terrific essays from another twelve writers and critics.

Revolution in 35mm: Political Violence and Resistance in Cinema from the Arthouse to the Grindhouse, 1960-1990 covers an incredibly broad and diverse body of cinema, spanning from the Algerian war of independence and the early wave of post-colonial struggles that reshaped the Global South, through the collapse of Soviet Communism in the late ‘80s.

It focuses on films related to the rise of protest movements by students, workers, and leftist groups, as well as broader countercultural movements, Black Power, the rise of feminism, and so on. The book also includes films that explore the splinter groups that engaged in violent, urban guerrilla struggles throughout the 1970s and 1980s, as the promise of widespread radical social transformation failed to materialize: the Weathermen, the Black Liberation Army and the Symbionese Liberation Army in the United States, the Red Army Faction in West Germany and Japan, and Italy’s Red Brigades.

Many of these movements were deeply connected with and expressed their values through art, literature, popular culture, and, of course, cinema. Twelve authors, including academics and well know film critics, deliver a diverse examination of how filmmakers around the world reacted to the political violence and resistance movements of the period and how this was expressed on screen. This includes looking at the financing, distribution, and screening of these films, audience and critical reaction, the attempted censorship or suppression of much of this work, and how directors and producers eluded these restrictions.

Shakedown is also available on YouTube.

Thank you for highlighting films that I love and are almost forgotten and books that people have skipped over. It feels good to meet a fellow soul, lol! I fell in love with John Le Carré a long time ago through a French translation of Tinker Tailor... I was transfixed but got the real shock when I snatched an original English copy of the book, so I grabbed everything I could find from the guy: Call for the Dead, a Murder of Quality, and yes, The Looking Glass War.... For the longest time A Small Town in Germany really hit me where it hurt... don't know why...